Research

My primary research focus is on compact binaries where a compact object, such as a white dwarf, neutron star, or black hole, accretes material from a companion star. Generally, this material from the donor has orbital angular momentum that must be transfered away in order to accrete, so that the infalling material forms a disk around the compact object. In some types of systems, the cold material reaches a critical temperature (the ionization temperature of hydrogen) and triggers a sudden heating of the disk and rapid accretion. These disk instabilities are responsible for dwarf novae in white dwarfs and so-called X-ray novae in neutron star and black hole systems. While white dwarfs and neutron stars can be found in isolation, we have only ever found galactic stellar mass black holes in these types of binary systems.

A major problem in studying the black hole population is that every stellar mass black hole in the Milky Way which has a robust mass constraint has been identified in outburst and followed into a quiescent state where the donor star becomes visible. Our population is, therefore, entirely premised on the event of a disk instability outburst. This large selection effect could have a profound impact on important scientific questions. For example, the current mass distribution of compact supernova remnants (neutron stars and black holes) has a gap from 2-5 solar masses. If this is real, it would have a profound impact on supernova physics. Finding new black holes for which mass measurements are possible and which avoids the selection effects of the current population is therefore a high priority for modern astrophysics. Optical spectroscopy and photometry are key tools to measure orbital parameters such as period, inclination angle, mass ratio of the two components, and individual masses.

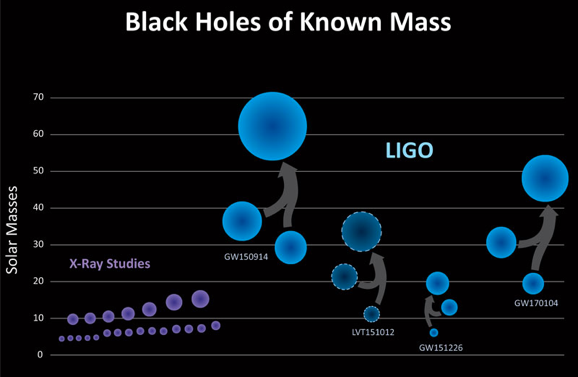

In addition to the dearth of low-mass black holes, the extraordinary results of the Advanced Laser Interferometer Gravitational-wave Observatory (aLIGO) have discovered stellar black holes more massive than any previously known from X-ray studies. Where do black holes this massive come from? Are they a result of previous black hole mergers, building up in merger trees to the giants that LIGO detected? Or are they born that large, perhaps as a result of the low metal content of their progenitors? Globular clusters are both high-density, high-encounter rate environments and have extremely low metallicities, so that these new aLIGO results give a new urgency to measuring the masses of the radio detected black hole candidates in globular clusters.

The mass distribution of neutron stars is also of fundamental importance. Neutron stars contain material at densities unlike anything found on Earth, fitting 1.4-2.0 times the mass of the Sun in a sphere with a radius of only 10-15 kilometers. Material at this density offers an excellent probe of the strong nuclear force at regions of phase space that are simply unattainable here on Earth. There are many different ideas about how material behaves at these densities, but so far there are not enough systems with known parameters to constrain the equation of state of neutronic material to any high degree. One reason for this is that some measurement must be made of both the mass and the radius of the neutron star, or some relationships between the two. These have been only weakly constrained for a handful of systems. Alternatively, the maximum neutron star mass varies depending upon the model used, so finding heavy neutron stars would eliminate some equations of state. Indeed, a 2 solar mass neutron star, which is an eclipsing 8 millisecond pulsar, has been identified with very precise limits in the last few years. The level of certainty on this high mass rules out many “soft” equations of state. There is still, however, merit in searching for neutron star masses both to fill out the mass distribution and because there is a chance we could find a neutron star with a still higher mass.

Currently, models of binary evolution predict wildly divergent end populations, consisting of white dwarfs, neutron stars, and black holes with and without companion stars. We only know of a relatively small number of each type of end scenario within the galaxy, which allows many models of binary evolution to offer predictions of population size differing by orders of magnitude while still avoiding conflict with existing data. Many of these end scenarios are semi-detached binary systems, which will tend to give off X-rays as matter from one star accretes onto the degenerate stellar remnant. The largest uncertainty in these models is in the common envelope phase of binary evolution. The energy lost in ejecting the envelope strongly influences mass and period distributions of low mass X-ray Binaries. It is in this phase that the system loses much of its angular momentum, allowing the formation of a close binary.

The relationship between radio and X-ray luminosities at the faint end of the luminosity range for compact binaries, particularly among new black holes discovered in quiescence but also in cataclysmic variables and the newly discovered transitional millisecond pulsars, promises new insights into jet launching mechanism. While the transitional milli-second pulsar track on the radio/X-ray luminosity plane seems to closely mirror the black hole track, the spectral and timing properties are different enough that distinguishing them for newly discovered objects should not be difficult, even without a mass measurement.

I am also interested in unifying accretion processes at all scales, from protostars to CVs to LMXBs. Time series data and radio observations will play a critical role in tying together outburst cycles, as the appearance of radio jets is tightly dependent on the state of the accretion disk. The appearance of transient jets has been observed in the CV SS Cyg as well as in BH and NS LMXBs,  while the new class of transitional milli-second pulsars has opened new questions about the reationship between radio and X-ray emission. Part of my work has examined X-ray / optical correlation, with some surprising results. For example, in MAXI and Kepler data , while one would expect the optical light to lead the X-ray by the viscous timescale as material works through the outer to the inner accretion disk, we found instead that the reverse was true – optical emission lagged X-rays by 12.5 hours. This result is still open to interpretation. Coordinated X-ray, UV, and optical observations will yield new insights into the cause of this peculiar behavior.

while the new class of transitional milli-second pulsars has opened new questions about the reationship between radio and X-ray emission. Part of my work has examined X-ray / optical correlation, with some surprising results. For example, in MAXI and Kepler data , while one would expect the optical light to lead the X-ray by the viscous timescale as material works through the outer to the inner accretion disk, we found instead that the reverse was true – optical emission lagged X-rays by 12.5 hours. This result is still open to interpretation. Coordinated X-ray, UV, and optical observations will yield new insights into the cause of this peculiar behavior.

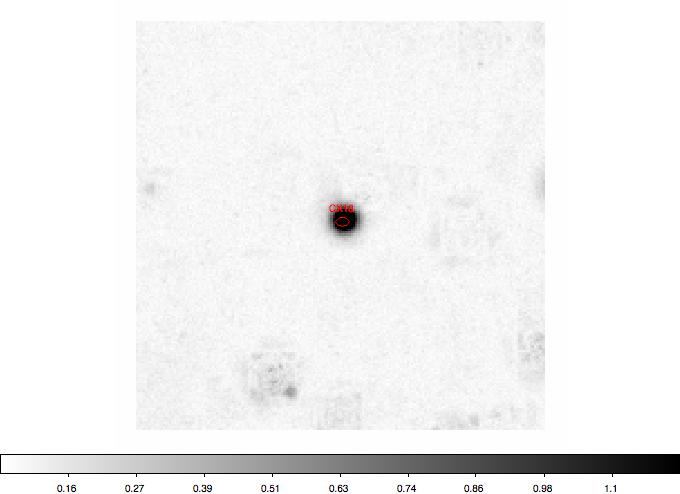

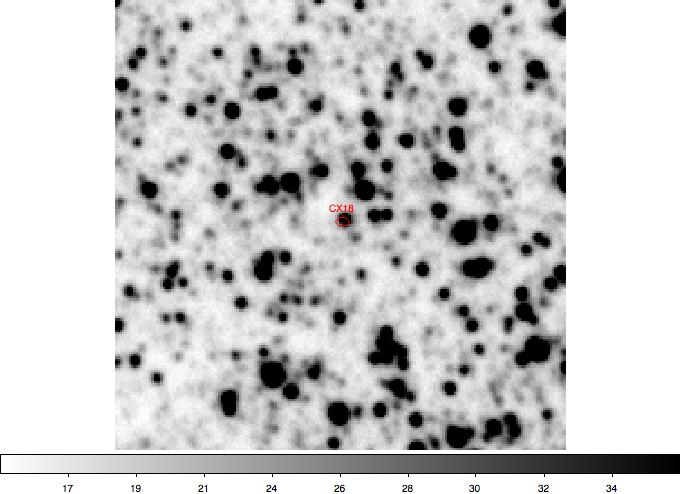

My work with the Chandra Galactic Bulge Survey has sought to use difference imaging of optical data, combined with an X-ray source catalog, to identify X-ray Binaries in quiescence in order to find systems without needing a recent outburst, which may be faint or infrequent for some systems. This wide, shallow X-ray survey has found many sources of X-rays beyond these X-ray binaries, including white dwarf systems, coronoally active stars in close binaries, and even some young stellar objects. The GBS covers a large area on the sky (12 square degrees) containing ~10% of the Milky Way's total stellar mass.

Our variability survey has only begun to scratch the surface of the science gains available in these observations. Already, we have demonstrated that large programs such as LSST can make significant progress in constraining the common envelope phase of binary evolution.

Our variability survey has only begun to scratch the surface of the science gains available in these observations. Already, we have demonstrated that large programs such as LSST can make significant progress in constraining the common envelope phase of binary evolution.

In my optical survey of the Galactic Bulge, I also found 8 X-ray detected white dwarfs accreting material in the GBS undergoing dwarf nova during the 8 days of optical observations. Recent work by Pretorius & Knigge (2012) and Byckling et al (2010) has constrained the X-ray luminosity function of CVs using a sample of nearby, well studied objects, which tells us the relative proportion of dwarf novae at different X-ray luminosities. I used the AAVSO archives to measure how often dwarf novae occur for these objects and have established a relation between the duty cycle and X-ray luminosity in quiescence of dwarf novae outbursts (Britt et al. 2015). Using this relationship and the X-ray luminosity functions established in Byckling et al (2010) and Pretorius & Knigge (2012), I simulated different sized populations of accreting white dwarfs to match the number of outbursts and X-ray detections we had in the GBS. In this way, I could measure the number of accreting white dwarfs undergoing dwarf novae relative to stellar mass in the direction of the Galactic Bulge. This is the first relationship between duty cycle of dwarf novae and X-ray luminosity to be made, and a constraint on the number of accreting white dwarfs at distances of thousands of light years (kiloparsec scales).

There is as yet no theoretical understanding of the relationship between the instantaneous mass transfer between the inner disk and the white dwarf (which causes the X-ray luminosity) and the relative balance between the material entering the disk and exiting the disk (which is responsible for the duty cycle).

There is as yet no theoretical understanding of the relationship between the instantaneous mass transfer between the inner disk and the white dwarf (which causes the X-ray luminosity) and the relative balance between the material entering the disk and exiting the disk (which is responsible for the duty cycle).

The next step for understanding these populations in the Milky Way is coming soon in the form of the Large Synoptic Survey Telescope. As a member of the LSST Stars, Milky Way, and Local Volume working group, I have pushed the science case for more extensive observations of the Galactic Plane than have been planned, and helped to write and evaluate metrics for what contributions LSST can make to questions of compact binary evolution. With eRosita producing an all sky X-ray source list down to the faint luminosities of quiescent X-ray binaries, LSST can identify optical counterparts and faint outbursts missed by All Sky Monitors. The huge amount of data produced by these surveys will finally bring a large part of the quiescent population of X-ray binaries under our gaze. By following the methods I outlined in the previous paragraph, taking advantage of the soon-to-come X-ray satellite eRosita, and the standard relationship betwee dwarf novae luminosity and orbital period, LSST can firmly nail down the cataclysmic variable population in our galaxy in 3 dimensions.

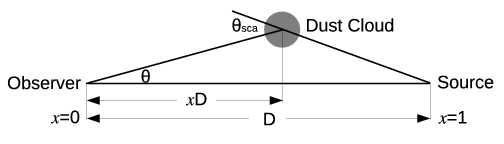

I also have an ongoing interest in using time delays to infer the geometry of systems, whether from dust scattering, reprocessing of light into longer wavelengths, or to track evolution of material through an accretion disk. The time domain offers a unique lever into the properties of a system, and stands to unify accretion processes at many different scales of size and mass.

Because light takes time to travel, the time delay between an initial signal and the scattered or reprocessed light from it can yield valuable insights into the 3D geometry of the system. This could, in principle, be used to measure the separation of binary componants, the distance to scattering dust clouds, or be used to study explosive events of ages past through their light echoes - a sort of archeological astronomy!

More generally, different wavelengths of light are emitted from different regions of the accretion disk, and studying the ways in which they correlate can tell us how material moves through and interacts within the disk.